Designing For Safety in Labor & Delivery

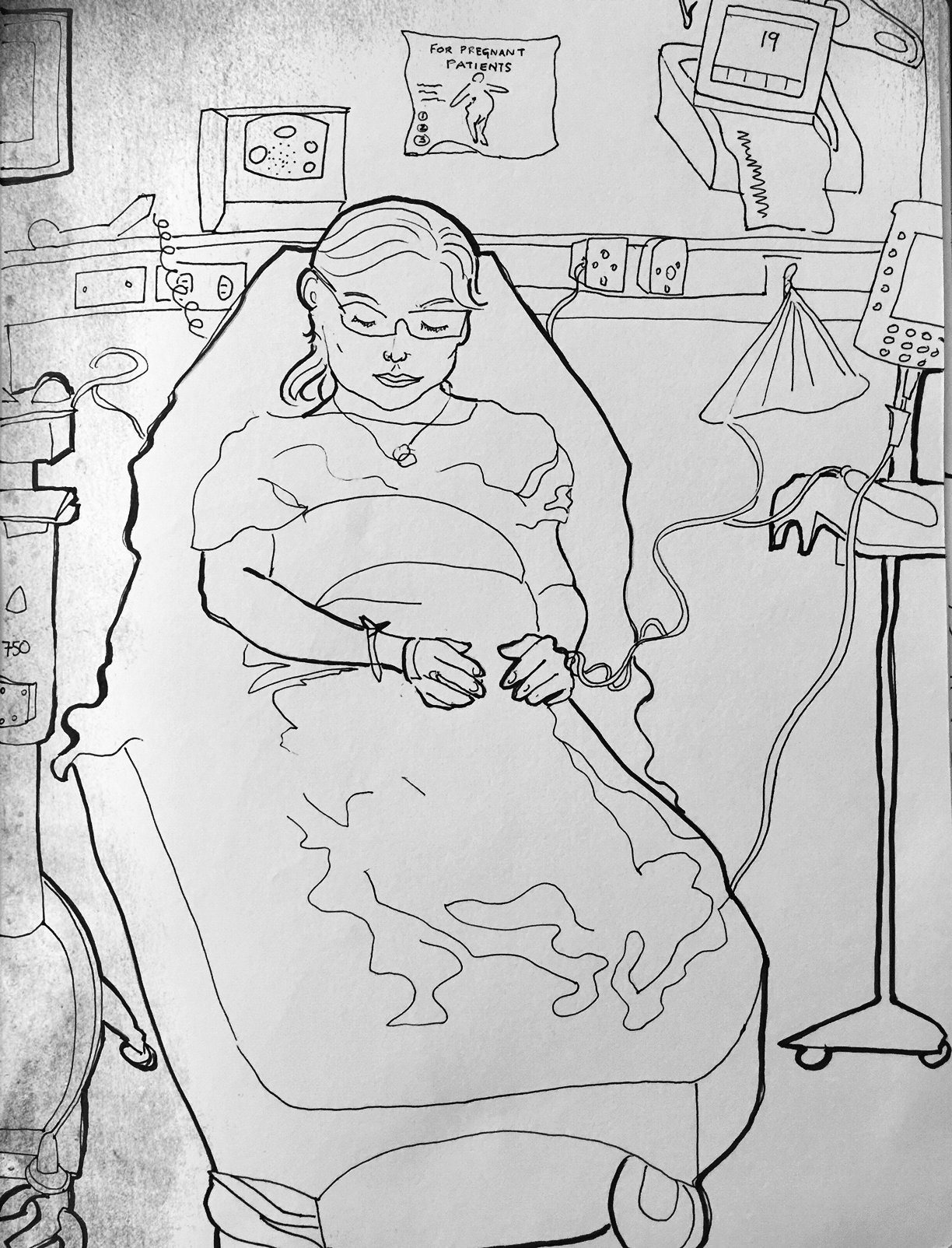

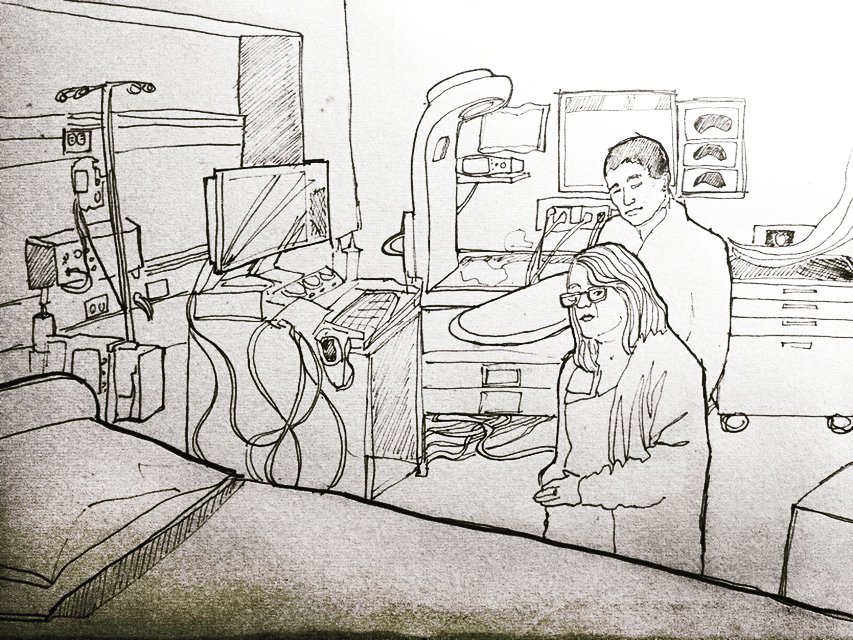

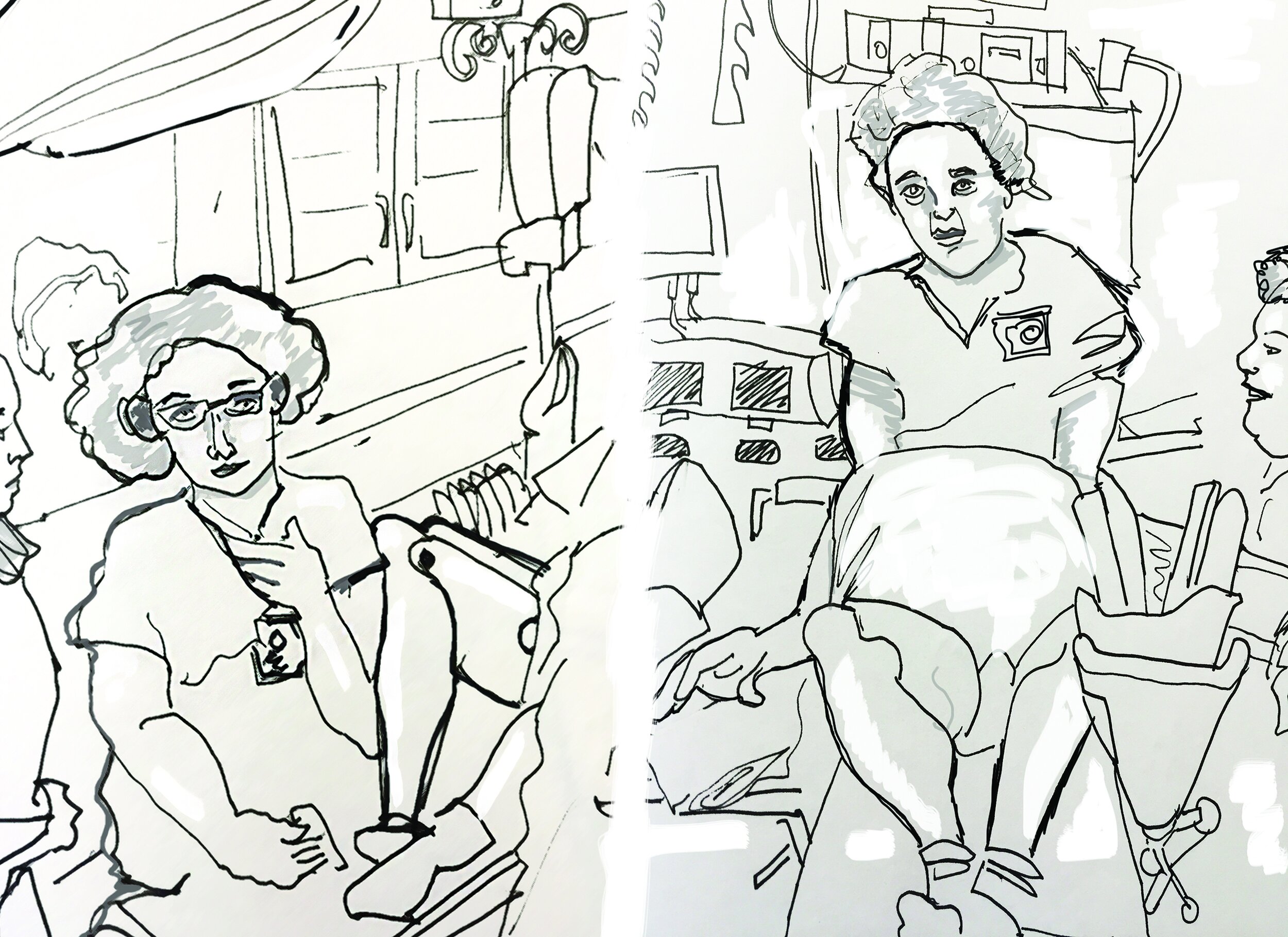

Drawn by Jules Sherman “Scenes From an OR”

A teaching team that combines a designer and a clinician is a must for classes in healthcare design and was, as a result, essential for creating a class like Designing For Safety in Labor & Delivery.

Clinicians are on the front lines everyday. They experience the problems first-hand and have excellent ideas for solutions. But they don’t have the time or skills to develop and implement those ideas. When teaching, I explain to new design students the value of naiveté and how it serves as an asset.

Understood as inexperienced visitors (who, in this case, are dropped into a complex healthcare setting), designers are “allowed” to ask many questions. Often those questions are met with answers such as, “It’s just how I was trained to do it, and I’ve never questioned it, even though it’s a difficult process.” Students learn quickly that clinicians are masters of creating, and putting up with clever, but often clumsy work-arounds, due to limited time for finding more sustainable solutions, budget issues, or physical space limitations. This is one of many lessons students learn, but there are so many more that I wish we had more time to convey. The academic quarter is so short that I often feel as if we were cramming too much information into a class. I want to allow enough time for students to fully experience the process of ethnography, synthesis, ideation, prototyping and testing. There is always a tension with time and teaching this process for me as an instructor.

We spoke to nurses at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital to understand the problems in their L&D unit

Empathy Map

The design-thinking methodology is not something you talk about; you have to do it in order to understand how well it works for solving difficult problems. This requires careful management of time in a 12 week class.

Synthesis work for developing a point of view

Many of my students continue their projects beyond our class in an independent study due to the time constraints of a single quarter. I remain a mentor in these cases, and connect them to the appropriate faculty who can sponsor them.

d. school students observing a simulated C-section birth at The Center For Advanced Pediatric and Perinatal Education (CAPE)

I am also constantly considering the question of how to effectively teach students in this particular context going forward. After this class, I am certain that simulation learning is the best way for design students to understand a clinical procedure, a work-flow, communication challenges, and the physical environment of a healthcare setting.

This is the second full-quarter class where we have used simulation learning at The Center For Advanced Pediatric and Perinatal Education (CAPE) at Stanford to illustrate challenging healthcare scenarios to interdisciplinary design students. I see the effect this kind of learning has on students. It’s very real. You are in the operating room watching a C-Section take place. The procedure is riveting because experienced doctors are performing the simulations. Students can walk around the simulated environment while the event is happening, take notes, capture photos and debrief with a video afterwards to analyze the event more closely. Through studying the medical simulations, students develop empathy for the clinicians and patients, and apply that knowledge to create products, services or systems that aim to improve safety and patient outcomes.

Observing a neonatal resuscitation at CAPE

In addition to forming working teams, the time constraints and creating the right learning environment, organization is the key to pulling off a class like this. Developing simulated medical events takes a lot of planning prior to the day of the simulation. We always practice the scenarios before the class so that the event goes as planned, and students are exposed to the highest fidelity simulation possible.

Ethnography was captured in sketchbooks

Also, enlisting clinicians that are truly passionate about design and improving processes creates an ambiance of focus and enthusiasm. Classes like Designing For Safety in L&D require initiating and cultivating many relationships with clinicians, patients and hospital innovation leaders. It takes a lot of passionate people to participate in a class that is human-centered, which is a requisite for every class at the d.school.

Debriefing at CAPE

Developing those relationships is a whole other set of skills beyond teaching, it’s the fostering of a community of individuals that care about healthcare improvement, education, and making a positive change in the world.

Students acting out “the problem” they are tackling in the sim lab